18/10/22

(Mis)understanding the Metaverse – A Thought Piece

Category

Written by

Read time

5 min

Metaverse Concept and History

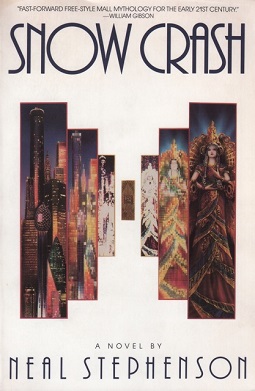

The term “metaverse” was invented by American author Neal Stephenson in his science fiction novel titled Snow Crash, published in 1992. In his book, the metaverse is a black spherical planet with one road that spans across the entire 2^16km circumference of the sphere. Real estate in this digital world is owned and sold through a fictional organization, and people can purchase that real estate to build structures atop of it. To access this metaverse, users must use proprietary virtual reality goggles and access a global fiber-optic network, which resembles today’s internet. Neal Stephanson called this 3D virtual reality world the “metaverse”.

Mixing the virtual with the physical has been pop culture trope in American television and media dating all the way back to the Back to the Future movie trilogy. In the second iteration of the blockbuster movie series released in 1989, young Marty McFly is seen wearing goggles that appear to let him interact with people who are not even in the room with him.

The idea of seeing a different world through proprietary hardware was not only a film trope, but also part of reality, when Nintendo released the first ever portable virtual reality gaming device, named the Virtual Boy in 1995. If we keep following the history of virtual reality, we eventually get to video games such as Second Life (2003) that created a virtual world for people to socialize and live in (which the creator Philip Rosedale admits was inspired by Snow Crash) and the development of consumer VR goggles, namely the Ocolus Rift (2012).

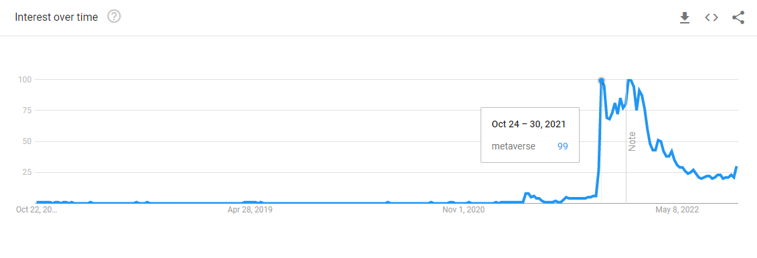

At this point, we had the technology to build virtual worlds as well as the hardware to transport our video and audio senses into these worlds, but the term “metaverse” only gained mainstream traction in late October 2021, when Facebook announced the rebranding to “Meta” and formalized their focus on the metaverse.

But with all the progress made, there was still one challenge: in Neal Stephenson’s book, people could own real estate, work and earn a living in the metaverse – people could actually live in it: the protagonist of Snow Crash is named Hiro, who is a pizza delivery driver and hacker in that very metaverse. Interactions like any other interaction in real life were possible in this world too, with value being traded between residents of this metaverse (time value of work for money, in the case of delivering pizzas).

It was not possible to prove unique individual ownership of digital assets, until Bitcoin came along and, with the invention of blockchain technology, made even that possible. Now that we have the virtual worlds, the technology to access them, and the decentralized networks that track value across these worlds, we are a step closer to reaching the original metaverse concept.

(Mis)understanding the Metaverse

At this point I would like to take a step back and ask you, the reader, this:

What is the end goal of the metaverse?

When you think of Meta, Sandbox or Decentraland, the idea of a metaverse may be a fictional universe where users are empowered to be who they cannot be, do what they cannot do, and experience what they cannot experience in the real world.

If we strip this concept of all its flashy parts that drive the marketing hype machine, specifically the “virtual reality” and “VR goggles” aspects, we get something far more interesting.

A system that allows us to interact with digital things the same way we do with physical things

In the physical world, if you have a football you can play any game with that football: you could play a match of football, you could kick it around or you could gift it to a friend, for example. The point is that you decide your interaction with the objects around you. There are no limitations in how you want to use the ball, and you can expect a certain level of privacy doing so.

In most virtual worlds today, interactions with digital objects are limited and carefully controlled. If you own a digital ball in one world, it’s highly unlikely you will be able to use that ball in another. Companies tend to build walled gardens, so that they can maintain control and ownership over all interactions within it. While this creates tailored experiences, once these virtual worlds are retired, everything that users built disappears in an instant. Imagine that ball you’ve played with all your life disappearing out of your closet, because the ball manufacturer decided it’s time to release a new ball.

Shouldn’t we be able to use and own digital assets in a similar way to physical assets?

Unlocking those capabilities is what I call true interoperability and what I believe the purpose of a metaverse should be. The virtual worlds that attempt to look real, the proprietary hardware to access these worlds – these are marketing hype for which interest will come and go as those technologies develop. However, the ability to interact within a digital system with the same freedom of will that we have in the physical world is what will drive adoption of these metaverses.

With Web3 technology and the open source movement, we are moving towards new systems that will form the foundation of a truly interoperable and flexible digital economy that mirrors the physical world.

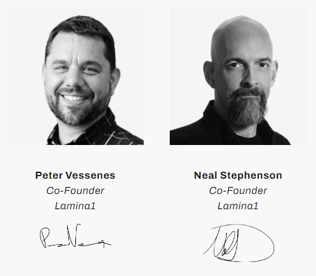

And in a somewhat ironic twist, Neal Stephenson, the author of Snow Crash, is working on his very own Layer1 blockchain called Lamina1, which sets out to achieve these goals.

The Metaverse represents the evolution of our lives online –– graduation to rich 2D and 3D worlds in which we fluidly create, explore, socialize and transact. As we usher in this bold new era of content creation and participation, we must revisit the centralized business models of Web2 to empower creators and consumers with greater agency, ownership and privacy. A creative community that is free to innovate and transact will give rise to a thriving economy. – Lamina1 Whitepaper

SHARE THIS PIECE

Related content

In this piece @lingchenjaneliu explores the staking market landscape, including key actors and top players, as well as latest developments in Proof-of-Stake. Special thanks to @0xPhillan for ...

The year of 2022 was a year of great highs and new lows for the Web3 industry. Read more about the defining events of 2022!

Short answer: Account abstraction creates a new account type which exists as a smart contract. By having the account exist as a smart contract, transaction ...

Wintermute, a crypto asset manager and liquidity provider, was recently hacked for US$160m. The hack occurred on their DeFi operations and did not affect other ...